Chupadero Mountain View RV Park - San Antonio, NM

San Lorenzo Canyon is

jointly managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Land

Management as a primitive recreation area. This scenic east-west canyon offers

ample outdoor opportunities for hiking and primitive camping. Not only a

destination for hikers, the Canyon offers outstanding opportunities for

photographers. Millions of years of Earth’s history unfold in San Lorenzo

Canyon, a picturesque area of sandstone cliffs, arches, and hoodoos. The cottonwoods

indicate there may have been a reliable water source at one time in the area.

The area has remnants of old ranches and homesteads; springs and tiny creeks

are hidden in the canyon bottoms and washes.

We made a short visit to the canyon after setting up Ethel and taking my post drive nap.

The canyon had a lot of beauty and definitely requires further investigation at a later date. There were a few boondockers camping, but otherwise, we had the place to ourselves.

The history of Chloride reads like the script for a bad western

– silver strike, population boom, Apache raids, salvation by the militia,

cattle versus sheep, tar and feathering, and even bear attacks.

An Englishman named Harry Pye was

delivering freight for the U.S. Army from Hillsboro to Camp Ojo Caliente in

1879 when he discovered silver in the canyon where Chloride is now located.

After completing his freighting contract, he and two others returned to the

area in 1881 and staked a claim.

The name "Chloride" was

finally selected, after the high-grade silver ore found there. It became the

center for all mining activity in the area, known as the Apache Mining

District.

During the 1880s, Chloride had

100 homes, 1,000-2,000 people, eight saloons, three general stores,

restaurants, butcher shops, a candy store, a lawyer's office, a doctor,

boarding houses, an assay office, a stage line, a Chinese laundry and a hotel.

Chloride and the surrounding area

began to decline with the silver panic of 1893, when the country went on the

gold standard and silver prices dropped about 90 percent. Today, about 27 of

Chloride’s original buildings are still standing, including the Pioneer Store,

which now serves as a museum. Main Street is lined with false front structures,

as well as adobe buildings, some restored and some suffering the effects of

time.

There are two cemeteries and the

200- year-old oak "Hanging Tree" tree still stands in the middle of

Wall Street. About 20 residents, many of who are descendants of the original

founders, occupy the town. The road abruptly ends at the edge of town. There is only one road that leaves and enters the town. Absolutely no one just happens to pass through Chloride, it is miles from the nearest town.

Edwin Berry (Baca), an iconic New Mexico penitente (member of a religious society that originated in Mexico. They practice self whipping and other forms of self torture and sacrifice during the Holy Week, hence the word penitence.),

folklorist and musician who revived a Holy Week pilgrimage to Tomé, a Spanish

land grant community nearly 300 years old and about 35 miles south of

Albuquerque in Valencia County. Every year many people of various faiths make the trek up to the sacred shrine for a spiritual experience. On Good Friday every year, people flood the area in a pilgrimage to the site in honor of Christ's death and resurrection. There remains about 1,800 petroglyphs dating back nearly 2,000 years ago left by the ancestral pueblo people.

Berry, who died in 2000, is credited with erecting a 3 cross crucifixion shrine in the late 1940s at the top of the volcanic hill, which he often

described as the perfect church: “Open to all, at all times, and no collection

plate.”

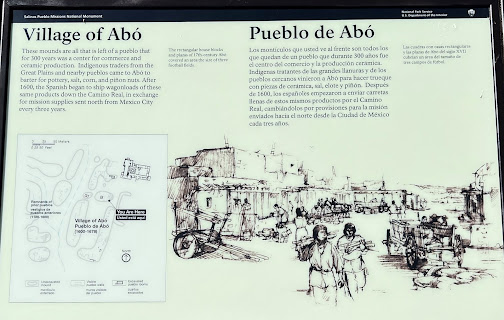

The Salinas Pueblo

Missions National Monument is a complex of three Spanish missions located

in New Mexico, near Mountainair.

Once,

thriving Native American trade communities of Tiwa and Tompiro

language-speaking Pueblo people inhabited this remote frontier area

of central New Mexico. Early in the 17th century Spanish Franciscans found

the area ripe for their missionary efforts. However, by the late

1670's, the entire Salinas District, as the Spanish had named it, was depopulated

of both Indian and Spaniard. What remains today are austere yet beautiful

reminders of this earliest contact between Pueblo Indians and Spanish

Colonials: the ruins of three mission churches, at Quarai, Abó, and Gran

Quivira and the partially excavated pueblo of Las Humanas or,

as it is known today, the Gran Quivira pueblo.

The Abo Pueblo community

was established in the 11th century on the edge of the existing pueblo culture,

and often attracted roaming Nomadic Tribes of the eastern plains.

San Gregorio de Abó Mission (located in Mountainair, New Mexico)

was one of three Spanish missions constructed in or near the pueblos of central

New Mexico. These missions, built in the 1600's, are now a part of the Salinas

Pueblo National Monument which includes San Gregorio de Abó Mission, Quarai and

Gran Quivera.

The mission at Abo was established in 1625 by Fray Francisco Fonte. He kept very meticulous written records of events at the mission during his time there. His records provide much information about life at the pueblo that would otherwise not be available.

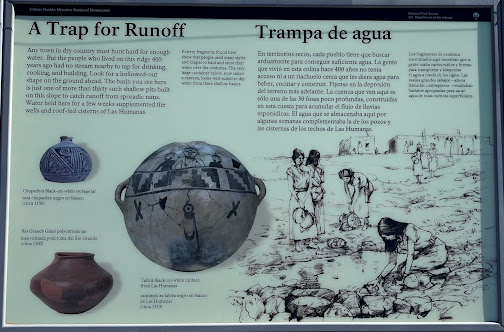

The Gran Quivira Ruins are

located about 25 miles south of Mountainair, at about 6500 feet above sea

level.

The Gran

Quivira, as it has been called for over a hundred years, is by far the best

known of the Salinas pueblos, and in fact is one of the most celebrated ruins

in all of the Southwest. It is altogether the largest ruin

of any Christian temple that exists in the United States. From the first, there has been the connection of glamor and romance and the strange charm of

mystery, which adds tenfold to ordinary interest. How and when it first

received its deceptive title of "Gran Quivira" we may never know;

there are dozens of traditions and theories and imaginings. From the days of

Coronado, the name of "Quivira" had been associated with the idea of a

great unknown city, of wealth and splendor, situated somewhere on the Eastern

Plains. It is not at all unlikely that when some party from the Rio Grande

Valley, in search of game or gold, crossed the mountains and the wilderness

lying to the east, and was suddenly amazed by the apparition of a dead city,

silent and tenantless. It bears the evidences of a large population, of vast

resources, of architectural knowledge, mechanical skill, and wonderful energy,

they should have associated with it the stories heard from childhood of the

mythical center of riches and power, and called the new-found wonder the Gran

Quivira.

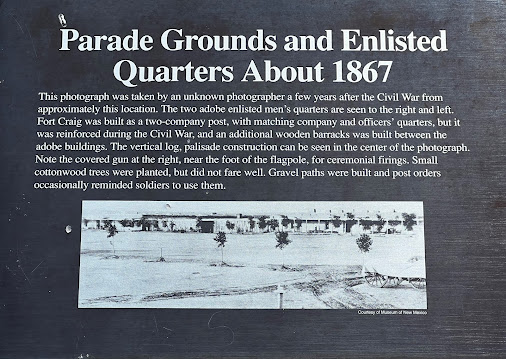

Fort Craig was a U.S. Army fort located

along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, near Elephant Butte Lake

State Park and the Rio Grande in Socorro County, New Mexico.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo called for the construction of a series of forts along

the new boundaries between Mexico and the United States. Apaches and

other Native American groups were reportedly harassing settlers and

travelers on both sides of the border. The attacks by the tribes from U.S.

territory into Mexico was a problem the U.S. government was obligated to

address under the treaty.

In 1849, an initial garrison was

established at Socorro, New Mexico. Fort Conrad was then established in 1851 on

the west bank of the Rio Grande near Valverde Creek. This was

near the north end of the Jornada del Muerto, which was an especially

dangerous segment of the major route known as the Camino Real de Tierra

Adentro. Although it was an ideal location from which to launch military

campaigns against the Apache and Navajo, Fort Conrad was beset by

construction problems and was under constant threat of flash floods, so it

operated for only a short while until a replacement was built several miles

away.

In 1853, the 3rd U.S. Infantry

Regiment began constructing a new fort on a bluff nine miles downriver

from Fort Conrad. The new fort was named in honor of Captain Louis S.

Craig, an officer in the Mexican–American War who had been murdered

by deserters in California in 1852. The new fort was garrisoned in 1854

with troops transferred from Fort Conrad.

Life at remote Fort Craig was uncomfortable and lonely at

best and deadly at worst. The buildings were a constant source of misery to the

soldiers, and records reveal litanies of complaints about leaky roofs,

crumbling walls and chimneys, crowded conditions and filth from crumbling dirt

roofs and muddy floors.

By July 1861, Fort Craig had become

the largest fort in the Southwest, with over 2,000 soldiers. That same year,

several regiments of New Mexico

Volunteers were established to handle the new threat posed by

the Confederate Army of New Mexico.

In February 1862, all five regiments

of New Mexico Volunteers were sent south from Fort Union to reinforce

Fort Craig and to wait for the Confederate advance up the Rio

Grande.

After capturing several military

installations in the newly established Confederate Territory of Arizona,

Brigadier General Sibley led his enthusiastic but poorly equipped

brigade of about 2,500 Confederate Army of New Mexico men. On

February 7, 1862, the Army of New Mexico left Fort Fillmore and

headed north towards Fort Craig, but marched well around the fort after the

Union Army refused to do battle on the plain in front of the fort.

On February 21, 1862, the Union troops

led by Colonel Edward Canby and the Confederate Army of New Mexico of

Brigadier General Sibley first met at the Battle of Valverde, a

crossing of the Rio Grande just north of the fort. Both sides took

heavy casualties. At the end of the day, the Confederates held the field of

battle, but the Union still held Fort Craig.

The Battle of Valverde is considered a

Confederate victory. However, the New Mexico Volunteers, under the command of

Colonel Miguel Pino, found the Confederates' lightly guarded supply wagons

and burned them. Sibley was forced to march further north without the supplies

he had hoped to take from Fort Craig. On February 23, 1862, the Confederate

forces marched around the Union Army and headed for Albuquerque.

Between 1863 and 1865, Fort Craig was

headquarters for U.S. Army campaigns against the Gila and Mimbres Apaches.

Fort Craig was permanently abandoned in 1885.

The BLM runs a visitor

center at the Fort Craig Historic Site, located 105 miles north of Las

Cruces and 32 miles south of Socorro.

At the Bosque del Apache

National Wildlife Refuge, the refuge offers unique bird and wild

life viewing opportunities each season. Peak visitation occurs in winter when Bald Eagles.

thousands of sandhill cranes and snow gees flock to the fields and marshes.

It is a very strange place- we are in the middle of the high desert yet there are marshes/swampy areas for waterfowl.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment